In Pursuit of Japaneseness with Yamaguchi Akira

I first met Yamaguchi Akira in a back room of the art gallery in the SOGO department store in Yokohama in May, 2013. It was the final day of a retrospective exhibition of the artist's work and Yamaguchi was on site to direct the deinstall. I'd seen the show about a week earlier, after visiting Yamaguchi's gallery, Mizuma Art Gallery, following up on the email inquiry I'd sent before leaving for my research trip in Tokyo. I'd been wondering if Yamaguchi-san would be interested in collaborating on my novel, contributing several images responding to my text that would be included alongside photos I'd take during my travels. I didn't receive a response before I left, so I figured I'd just stop by Mizuma at some point and make my inquiry in person.

Mizuma Art Gallery is a relatively small upstairs space, beside what remains of an Edo-era canal, cloistered behind a rather imposing steel door. There was a show of haunting paintings by O JUN on, and I wandered around taking them in while a young woman who worked there was finishing up a conversation with a tall Japanese—an artist, I imagined, as I'd become accustomed, in my linguistic isolation, to assigning roles to people I observed from a distance. The young woman, Miho Osada, spoke English and turned out to be Yamaguchi's representative. She hadn't seen my email but asked me to send it to her directly and said she'd inquire with Yamaguchi-san about his interest. She asked if I'd visited his show at SOGO and kindly gave me a ticket. He would be there the following week, she said, so if all went well maybe we could meet then.

The SOGO show was remarkable for its variety and size, including video, illustrations, and a few architectural pieces (such as a temporary tea ceremony room made mostly of corrugated plastic), in addition to paintings, the earliest of which (from the late 1990s) I'd seen in Yamaguchi's first book in English and Japanese, The Art of Akira Yamaguchi, and online, pieces that had first caught my attention a couple of months earlier as I was looking through the catalogue for "Bye Bye Kitty!!!," a 2011 show that had opened at New York's Japan Society just a week after the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. "Bye Bye Kitty!!!" was intended to introduce audiences to a new generation of contemporary Japanese artists, following in the wake of the seemingly exclusive international popularity of Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara, big names and personalities who'd built their reputations exploiting the kawaii (cute) popular culture of 1990s Japan, often developing its twee surface and erotic undertones in sometimes monumental and perverse ways.

Yamaguchi earned mentions in both the New Yorker and New York Times reviews of "Bye Bye Kitty!!!," and was labeled a humorist by Peter Schjeldahl, apparently because of the often comic effect of his revival of Heian-era (794-1185) techniques, namely fukinuki-yatai (“exploded roof” perspective) and rakuchū rakugai-zu ("scenes in and around the capital"). The Yamaguchi images accompanying both reviews, Narita International Airport: View of Flourishing New South Wing and Narita International Airport, Various Curious Scenes of Airplanes (both from 2005), displayed both techniques, providing cutaway views of the airport and the circling planes, respectively, revealing inside a panoply of figures, as Heian yamato-e (Japanese-style, as opposed to Chinese-style painting, focused on Japanese subjects and themes) might have provided a record of different types of people who inhabited a palace in Kyoto. Yamaguchi's paintings seem similarly documentary in this sense, though his types are drawn not just from the contemporary world, but from almost the entire history of Japan. In Narita International Airport, Western tourists chat beneath a chandelier on the upper deck of one circling 747, while on the deck below, Heian-era nobles sit down to a candlelight dinner and salarymen roll up their sleeves in an adjoining poolroom. In another jet, passengers in contemporary and ancient dress drink tea around a Japanese garden lit by skylights.

Interestingly, though one may experience the same mashup of temporality (in terms of dress) walking through Ginza today, attire in Yamaguchi's paintings does not strike one as costume. It is the age itself, so the effect is that past, present, and future co-exist in these and many others of his images. Not just in the human realm, but also in architecture, with electrical poles acquiring stylized roofs and ornaments normally seen on shrines, and glass towers sprouting antennae, radar dishes, and defensive weaponry. The SOGO show included several of Yamaguchi's battle images, too, in which, again, the historical and the contemporary are mashed up, as in the bodies of mechanized horses that seem strangely organic, despite having a single motorcycle wheel in place of their legs, or having been opened up on one side to reveal a compact kitchen to feed the warrior on the go. The steed as bento box.

The artist's sense of humor—ironic, maybe more generous than acerbic—is evident in the images' subjects, construction, and style. But there were plenty of images in the SOGO show that were more serious, too, or at least more ambiguous in tone: manga-like evocations of Buddhist deities; flowers whose stems and buds are connected by mysterious wires; side-by-side drawings in which an everyday object, a wall or a TV remote, is transformed by the artist's eye into a battleship or a space cruiser. The ease with which Yamaguchi's reproductions (quotes or copies, essentially) of traditional subjects (even nature) sprout sci-fi fixtures, collapsing time once again, do always seem humorous or amused, but also searching. As much as his embellishments represent the play of a creative mind (an inventor's mind; Yamaguchi is a master draughtsman and there's a very precise schematic quality—an architect's, an engineer's—to all of his work, even the most painterly), there's also a sense that the futural has always existed in the mannered gestures of traditional Japanese images, that it's merely a matter of extending the conceit of yamato-e a little further until the present and the future emerge, seamlessly, from the past, like wires from a flower stem. Or is the suggestion that some kind of mechanization lies behind every Japanese surface? That every sublime landscape is constructed? (There is some truth, and history, in this.)

Maybe a central subject (one of many) in Yamaguchi's work is not satire so much as continuity. Even despite the individualism of each of the multitudinous figures in works like Narita International Airport or the rooflines of his Tokei (Tokyo) series, showing different views of the capital (in the manner of Edo-period artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige), there's also a hypnotic serial quality to the crowds and the architecture flowing endlessly across the picture surface, sometimes disappearing as they approach the stylized shape of a cloud or the canvas edge: an abstraction, a pleasing blankness, a dream Tokyo, an idea of Japan, of Japaneseness. The viewer's eye quivers between the micro- and the macroscopic. The body wants to step forward to appreciate the precision of the minute detail, but also, simultaneously, to step back to contemplate the ingenuity of the overall design. In subject and style, as well as in Yamaguchi's method of quotation, there seemed to me to be a quality of playful self-reflection (cultural rather than personal) that made him the perfect match for what I was after in TOKYO: a respondent to my imagined Tokyos; not an illustrator of my inherently Western vision, but an artist whose subject, like mine, is the notion of Japaneseness, the internal compaction of history that contextualizes contemporaneity's outward performance—only he is actually Japanese and could expose, in his vision, all that I couldn't, as a Westerner, see.

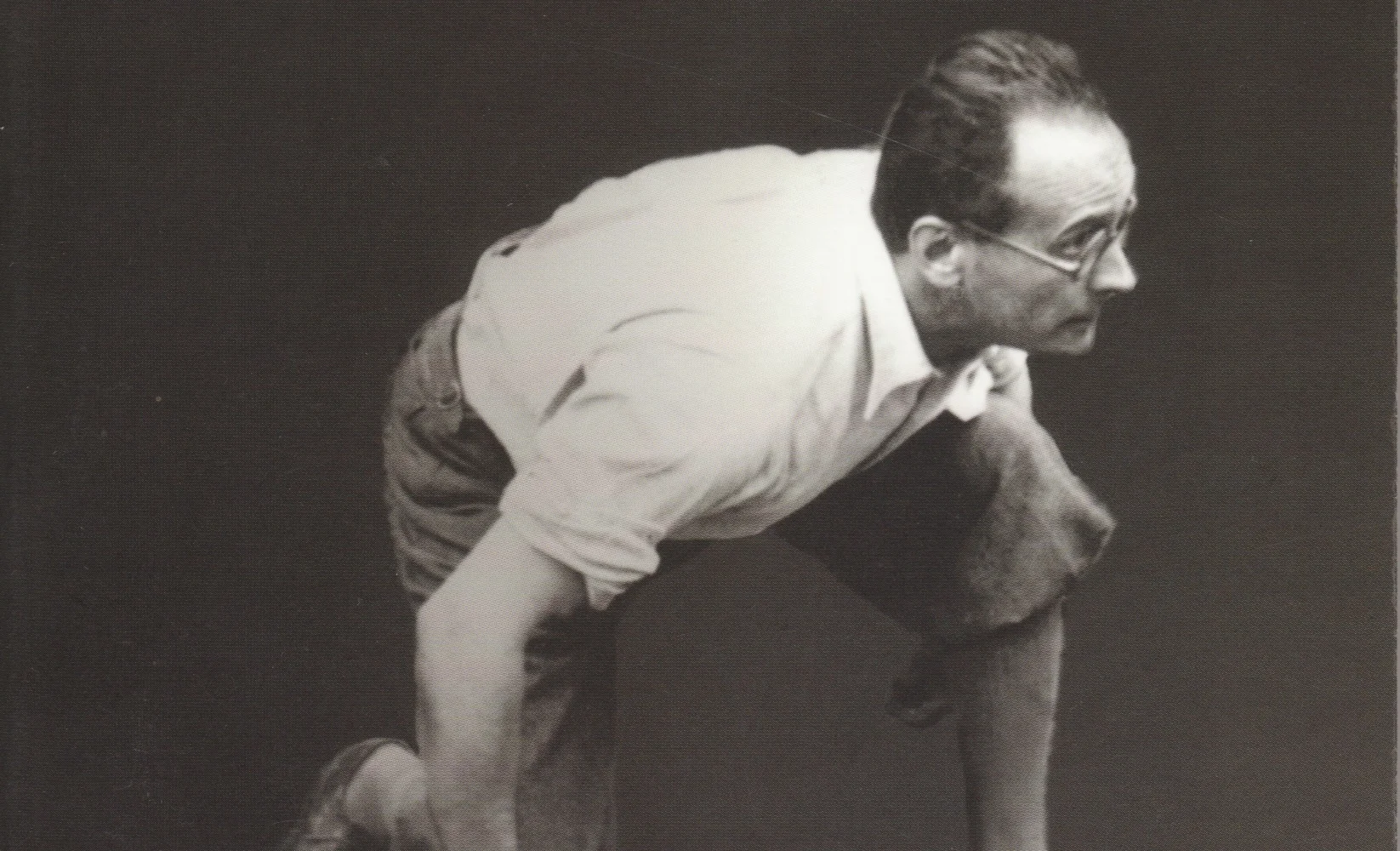

And Yamaguchi-san, in person, did indeed strike me as supremely Japanese, in a way that was both natural and self-aware. May is an increasingly warm and muggy month in Tokyo, and it was a bit a close in the SOGO gallery back room. In the middle of our conversation, Yamaguchi-san drew a plain paper folding fan from his bag and casually fanned himself. This was not a common gesture; I never saw another Japanese use such a fan. But this was also not a performance for my or for anyone else's benefit. It was a wonderfully stylish, but perfectly utilitarian anachronism. Also, note that, when I use his full name, I always refer to Yamaguchi-san by his last name first. This, I read in an interview or some essay, is something he's insisted upon, even in Western publications (the title of his first book notwithstanding): retaining the Japanese order of his names. So it seems to me that Japaneseness and what it means to be Japanese is certainly a central concern of his art and life.

Predictably, however, there is still another tension—both personal and practical—around Japaneseness that I had not recognized in Yamaguchi's work when we met. As he has noted in several interviews, his college art training was in Western practice (introduced to Japan during the Meiji period, 1868-1912), and he has described arriving at a "dead end" at one point, unable to see how to proceed with a career as a Japanese artist with an "independent aesthetic," how to reconcile the methods, materials, and expectations of Western art with his identity and interests as a Japanese. "Some of the techniques I use are borrowed from traditional methods," he says in a 2013 interview with Brigitte Koyama-Richard, "but basically I’ve considered myself a contemporary Japanese artist ever since I first encountered Western-style painting."

The problem of Yamaguchi's "dead end" went deeper than the choice of subjects and materials. He was wrestling, too, with the Japanese attitude of reverence toward Western art and artists as superior, as more sophisticated and advanced, as inevitably contemporary, which Yamaguchi says has persisted ever since the Meiji government embarked on its program of rapid modernization in all areas of political, industrial, military, and cultural life, preferring the most "advanced" Western methods as measures of progress, while reforming or scuttling traditional Japanese practice along the way, labeling these, as the West had, as barbaric.

Yamaguchi describes his college-age attitude toward this approach as "skeptical," but he seemed to have little sense of an alternative, of an alternative present and future for himself without a deeper connection to what Japaneseness had meant prior to the opening of the country in the mid-19th century. "Most of the mental images I had of pre-modern Japan came from watching old Kurosawa movies," he told Koyama-Richard—until he had a chance encounter with a show of yamato-e paintings. "I was stunned by the boldness of the composition," Yamaguchi says. "And then it hit me: 'This is it!' I wanted to try to find a way into traditional Japanese painting as it was back before Western art reached Japan. In other words, I wanted to re-do the modernization of Japanese art for myself."

To some extent, though, these were ultimately technical and aesthetic problems or questions, not personal ones. Yamaguchi-san appears, to me, undoubtedly Japanese, and he may insist (overtly and less so) on his own Japaneseness (the order of names, etc.), but he also seems to understand his identity as inherently hybrid, just like the two approaches to art that have shaped his career.

After being under the illusion that there was an innate Japanese quality in me, I realized that I was actually pretty empty when re-experiencing the Western stuff. And through the course of combining Japanese and Western methods, I also realized that Western painting didn’t necessarily have originality either, but had appropriated different elements. So had Japanese art, of course. I now think appropriation is a rather natural act, and such a dichotomy between the two has become a bit blurry lately.

So while I'd assumed wrongly a certainty of Japaneseness about Yamaguchi-san, my sense of his appropriateness for my project was still correct. More than a stable idea of identity as a Japanese (continuous with the Japanese artists of the past), what had attracted me to his work was his dynamic experiments in appropriation and mashup—fundamental techniques of my novel—which, as I've said, had deeper roots than I'd imagined. His own questions about what Japaneseness is or could be (an unresolvable formula) actually mirror mine, I think, though they come from a much more authentic well of experience and attachments (physical, psychological, aesthetic, philosophical, etc.), and from very different points of reference—exactly those I'd hoped would infiltrate the book. It can only be an imperfect mirror between us, after all, even if our questions and conceptual methods might appear similar, and it's this dissonance that I wanted to echo through TOKYO.