What's Your Book About?

Publishing with independent presses, we end up doing a lot of the post-publication hustling ourselves anymore: making noise about the forthcoming book; making inquiries with review venues; setting up readings; creating our own mini-tours, if we have the time and stomach for it. You could hire a publicist, of course, but I'm not complaining. As with acting in the role of editor and publisher, it's kind of great experiencing all aspects of the process, thinking creatively with every step, considering all the questions that could and should be asked—it's just time consuming. But it's your show to tailor as you like. You're asked (you ask yourself) to think again and again about the book: who might be interested and why, what's the draw, what's it about? (This could be phrased, "How do you/we sell this?" I'm not inclined think it that way, but it's there.)

I was asked by my university, in advance of a notice in its campus communications about TOKYO (also announcing my upcoming local book launch), for some information about "your book topic, what interested you in that, your research process, and what you hope people will take away from the book." All reasonable questions given the venue and audience. My response was too long, I knew, but I wanted to take the questions seriously and give the writer plenty to work with. Not exactly an elevator pitch, I guess, but it was a pleasure to reflect on my motivations and methods for awhile. Going up!

Much of TOKYO is focused on Tsukiji, the Tokyo Central Wholesale Market, the largest fish market in the world, which distributes more than 1500 tons of seafood, shipped from all over the world, to restaurants, supermarkets, and neighborhood stores every day—just to Tokyo and its suburbs. Because freshness is imperative, as are consumers' shopping and dining schedules, the market's selling day begins very early in the morning, and the seafood is delivered and prepared throughout the previous night, beginning at about 6 PM. When I first read about Tsukiji in a National Geographic article in the mid-1990s, I was fascinated by the quantities and varieties of seafood represented there, but also by what amounted to a small village (the market employs tens of thousands of people) living an opposite life to the metropolis around them—a 6 PM to noon life, essentially—and I wondered how that life might affect one's personal and community relationships. And what did it mean to be burdened by the responsibility of feeding, safely, that community you couldn't really participate in otherwise, but in which you played a fundamental role. (Tokyo is one of the world's largest cities and among the most densely populated, particularly during the day.) These were some of the basic questions behind the opening section, "Report of Ito Sadohara, Head of Tuna, Uokai, Ltd., to the Ministry of Commerce, Regarding Recent Events in the Domestic Fishing Industry," which I wrote several years ago, a narrative about a strange defect discovered in some bluefin tuna, written in the form of a report by a Japanese businessman, a high-level salaryman at a fictional tuna wholesale company.

While I wasn't a big sushi eater at the time (I am now—though I try to avoid bluefin because of overfishing), I'd had a thing for Japan since I was a kid. I grew up in Sacramento, CA, and many of my friends were second- and third-generation Japanese, Chinese, and Korean. So when I'd visit their houses, I'd see all sorts of artifacts of this heritage, even if they and their families were otherwise completely assimilated, American. There were plenty of Japanese films on television and in local art theaters, and as I got older I was reading Japanese authors in translation: Akutagawa, Kawabata, Kobo Abe, et al. My interest, to some extent, was in what I perceived as Japan's strangeness and seeming exoticism, probably not all that different from the interest of Americans in the mid-19th c., when Japan had been mostly closed off to the West by its military government. Scant details of the secretive archipelago were known from reports and rumors from Dutch merchants or sailors, often whalers, who'd been forced ashore by storms, although landing had been forbidden by the ruling shogun. Once Japan was essentially forced "open" by the American Commodore Perry in 1854, there was a massive influx into the country of Western missionaries, educators, merchants, and industrialists, happy to assist with the new emperor's desire to modernize (to put Japan on equal footing with the West in order to stave off the colonization that was happening in neighboring China). The "opening" fed a Western aesthetic and spiritual hunger, as well, leading to movements in art and décor, theater, and literature, an appropriating, distorting Japonisme, and endless efforts at interpreting the Japanese way of thinking and being.

Some years after finishing my salaryman's report, I felt like I'd perpetrated a similar kind of Japonisme in my creation of that character's voice, which was based on cultural research as well and on mining, mimicking, and parodying my favorite Japanese literature in translation. That's when I began to conceive TOKYO as a novel, a project that would begin to investigate, through fiction, the Japan I'd imagined, while also recognizing that every Japan I imagined would always already be a fictional one, a Western one. The last two sections of the book imagine a fictional American author, M, married to a Japanese-American woman, summoned to Tokyo for a potentially erotic relationship with a Japanese of indeterminate gender. Complicating things further (because, honestly, that's just my way) M's wife had been previously married to a salaryman very like the one who wrote the (fictional) report. So that document and its characters and sites and assumptions come under repeated scrutiny. What, I wonder, was I up to in imagining Japan and the Japanese in this way, and what am I still up to? What can I and can't I understand, not so much about Japan, but about my fascination with the place, the people, the culture? It's the Western fascination with Japan that's being examined, as well as the culture of consumption and ecological depletion and disaster that links us.

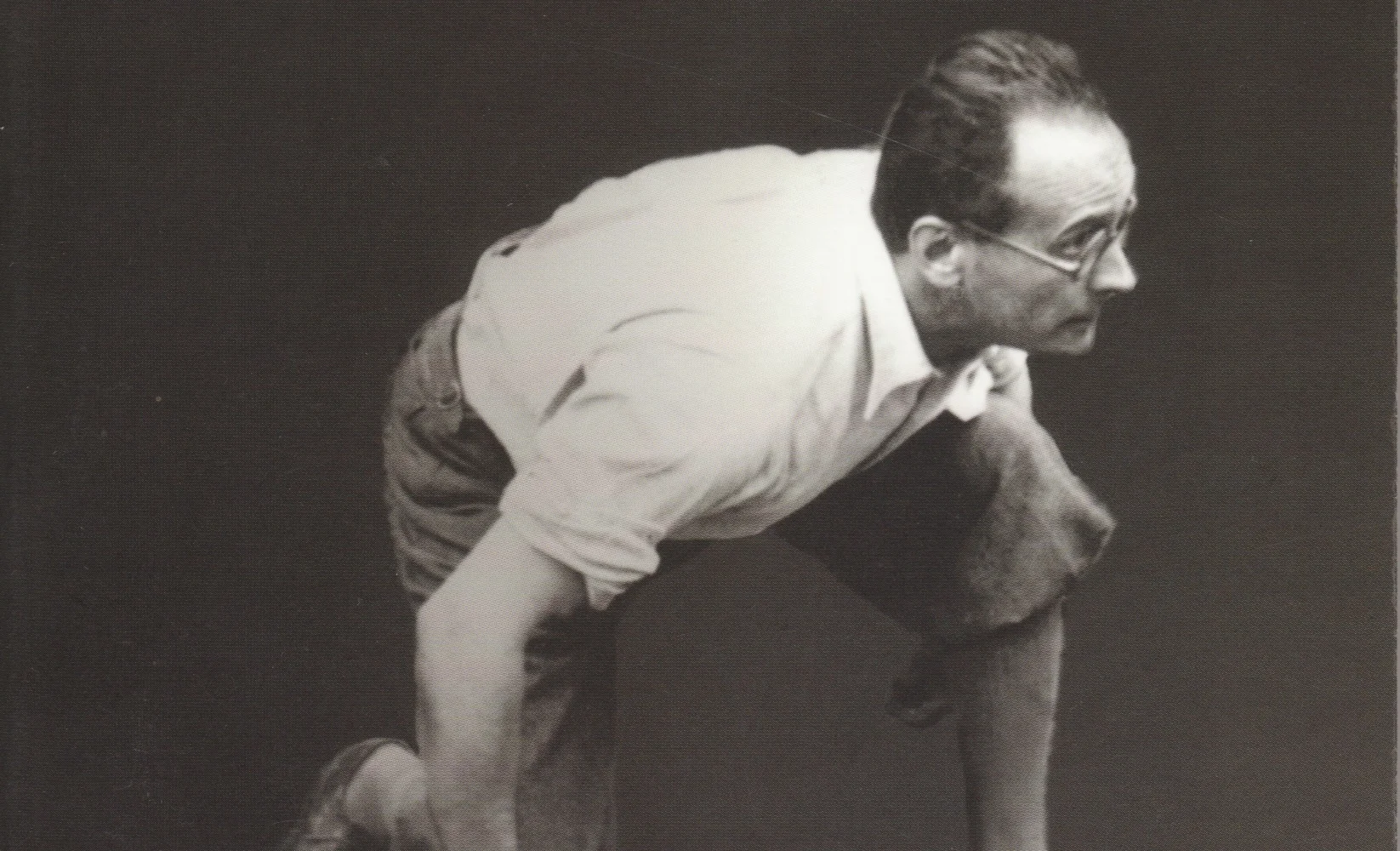

As I suggested, my research process involved a lot of reading, including Japanese fiction, nonfiction, and poetry from Bashō to Haruki Murakami, and Western writing about Japan from cultural critics like the legendary Donald Richie, and, very importantly, Theodore C. Bestor's Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World, an amazing sociological study of the market's intricately layered culture. I had never been to Japan when I wrote that first section, and I thought if I was going to really get at my obsession, I should go experience the place, imperfectly, to see what I imagined correctly (so far as I could tell) and also what I got wrong, and to continue to be wrong, to be the alien, to understand myself as such. I'm deeply grateful to Utah's University Research Committee (URC), the Asia Center, and the College of Humanities for grants that allowed me to spend a month in Tokyo, which provided me a lot of the details of place, and some partially fictionalized encounters, as well as all of the black and white photos and the six full-color images produced by Japanese artist YAMAGUCHI Akira that appear in the book. The images were really important to me. I wanted to create some tension between the fantastic, imagined Tokyo I was creating in words and the "real" Tokyo documented by the photos. And Yamaguchi-san's images are intended to suggest a further step: an authentic Japanese vision to translate my inevitably Western, fictional Japan. The URC grant also helped me pay for a translation of the report for Yamaguchi-san, who doesn't read or speak English, so that he could create those color images.

In terms of what I hope people will take away from the book, there is certainly the connection between our consumption and our bodies and all the other bodies in the world, animal bodies, and the inanimate, too. It's the shock of an inexplicable body that begins this reverberation in the book, but that extends to the shocking abundance of the market and the devastating cost to habitats (not fisheries) around the world as a result. I'm not intending an indictment of the Japanese or Japanese food culture. The idea is much bigger than that, Tsukiji providing only an extreme example, and one that couldn't exist without the participation of pretty much every other nation on the planet. Alongside this is something about bodies, about gender and race, and how we conceive of and talk about these, how we imagine them, and why we imagine them the way we do. I frame this as an erotic dialogue, because I do think there's love there, as well as violence and fear. Tsukiji is, finally, a bloody and violent place. But what I felt there, watching bodies sawed and chopped and stabbed, was hunger, desire. I guess I'm hoping for more love all around, and imagination, when it comes to bodies, all bodies, the connections between them, and the places they live, where they live best. I love feeding an appetite that can be fearsome, awful, but sometimes I think we should also learn to go hungry. There's an uneasy middle ground there, hard to maintain, but all the more enlivening for it.